MA Emilio Schmidt

Introduction

This master's thesis investigates the dynamics and stability of filamentary gas structures using numerical simulations. These filaments are of physical interest because they are common sites of star formation.

As a theoretical reference, this work builds on the analytically derived magnetohydrodynamic models of Fiege and Pudritz (2000a). They solved the stationary magnetohydrodynamic equations for cylindrical, self-gravitating filaments with helical magnetic fields and obtained equilibrium solutions from them. Building on these equilibrium solutions, they performed in Fiege and Pudritz (2000b) a linear stability analysis to investigate instabilities that occur, associated growth rates and characteristic wavelengths.

The aim of this work is to numerically reproduce the equilibrium solutions described by Fiege and Pudritz (2000a). These equilibria are then disturbed in order to investigate the temporal development of the disturbances and compare the results with those of the linear stability analysis by Fiege and Pudritz (2000b).

Theoretical Framework

The isothermal self-gravitating cylinder

Sought is the stationary density profile \(\rho\) of an infinitely long, isothermal, self-gravitating gas cylinder. To do this, the hydrostatic Euler equation has to be solved, which is given by:

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\nabla} P = \boldsymbol{f}_\text{ext} \end{align}

Here, \(P\) is the pressure field and \(\boldsymbol{f}_\text{ext}\) is the force density acting on the gas. In the considered case, this is the gas's own gravity. Since the gravitational field is a conservative force field, it can be expressed by a potential \(\phi_\text{ext}\):

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{f}_\text{ext} = - \rho \boldsymbol{\nabla} \phi_\text{ext} \end{align}

Inserting yields:

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\nabla} P = - \rho \boldsymbol{\nabla} \phi_\text{ext} \end{align}

The pressure field of the gas under consideration can be described by the equation of state of an isothermal gas, which is given by:

\begin{align} P = \frac{R T}{M} \rho \end{align}

Here, \(R\) denotes the universal gas constant, \(T\) the spatially homogeneous temperature distribution, and \(M\) the molar mass of the gas. Inserting into the hydrostatic Euler equation yields:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \frac{R T}{M} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \rho = - \rho \boldsymbol{\nabla} \phi_\text{ext} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \frac{1}{\rho} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \rho = - \frac{M}{R T} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \phi_\text{ext} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \boldsymbol{\nabla} \ln(\rho) = - \frac{M}{R T} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \phi_\text{ext} \\[6pt] \Rightarrow\;& \Delta \ln(\rho) = - \frac{M}{R T} \Delta \phi_\text{ext} \end{align}

It proves useful to use the Poisson equation of Newtonian gravity, which is given by:

\begin{align} \Delta \phi_\text{ext} = 4 \pi G \rho \end{align}

Inserting yields:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \Delta \ln(\rho) = - \frac{4 \pi G M}{R T} \rho \, , \quad \text{def.:} \, a := \frac{4 \pi G M}{R T} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \Delta \ln(\rho) = - a \rho \end{align}

For an infinitely long, straight, self-gravitating gas cylinder without an externally imposed azimuthal or axial structure, there is symmetry with respect to rotation about the cylinder axis and translation along the axis. The underlying equations share this symmetry, which is why corresponding derivatives disappear in the considered equation:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \frac{1}{r} \partial_r \big(r \partial_r \ln(\rho)\big) = - a \rho \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \partial_r \bigg(r \frac{\partial_r \rho}{\rho}\bigg) = - a r \rho \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \frac{\partial_r \rho}{\rho} - r \bigg(\frac{\partial_r \rho}{\rho}\bigg)^2 + r \frac{\partial_r^2 \rho}{\rho} = - a r \rho \end{align}

Due to the symmetry, the quantities considered depend only on the radius \(r\). Therefore, in the differential equation considered, the partial derivatives can be replaced by total derivatives:

\begin{align} \frac{\text{d}_r \rho}{\rho} - r \bigg(\frac{\text{d}_r \rho}{\rho}\bigg)^2 + r\frac{\text{d}_r^2 \rho}{\rho} = - a r \rho \end{align}

Since the density is positive by definition, the following substitution can be made without restriction:

\begin{align} u(r) = \ln\left(\frac{\rho(r)}{\rho_0}\right). \end{align}

Here, \(\rho_0 = \text{const.} > 0\) is a constant reference density. Its specific value is irrelevant for further consideration. It only serves to ensure that the argument of the logarithm is dimensionless. The first two derivatives of the new quantity \(u\) are then given by:

\begin{align} \text{d}_r u = \frac{\text{d}_r \rho}{\rho} \quad \text{und} \quad \text{d}_r^2 u = \frac{\text{d}_r^2 \rho}{\rho} - \left(\frac{\text{d}_r \rho}{\rho}\right)^2 \end{align}

Inserting this into the differential equation under consideration yields:

\begin{align} \frac{\text{d}_r u}{r} + \text{d}_r^2 u = - a \rho_0 \exp(u) \end{align}

To simplify this equation further, another substitution is performed:

\begin{align} z = u + \sqrt{2} t \, , \quad \text{with} \, t = \sqrt{2} \ln\left(\sqrt{a \rho_0} r\right) \end{align}

With \(\text{d}_r t = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{r}\), the following applies for the first two derivatives of \(u\) with respect to \(r\):

\begin{align} \text{d}_r u = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{r} \text{d}_t u \quad \text{and} \quad \text{d}_r^2 u = - \frac{\sqrt{2}}{r^2} \text{d}_t u + \frac{2}{r^2} \text{d}_t^2 u \end{align}

Inserting yields:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& 2 \text{d}_t^2 u = - a \rho_0 r^2 \exp(u) \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& 2 \text{d}_t^2 u = - \exp(z) \end{align}

Furthermore, the following applies:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \text{d}_t^2 z = \text{d}_t^2 u + \sqrt{2} \text{d}_t^2 t \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \text{d}_t^2 z = \text{d}_t^2 u \end{align}

Thus, it follows that:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& 2 \text{d}_t^2 z = - \exp(z) \\[6pt] \Rightarrow\;& 2 \left(\text{d}_t z\right) \left(\text{d}_t^2 z\right) = - \left(\text{d}_t z\right) \exp(z) \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \text{d}_t\left(\left(\text{d}_t z\right)^2 + \exp(z)\right) = 0 \\[6pt] \Rightarrow\;& \left(\text{d}_t z\right)^2 + \exp(z) = c_1 \, , \quad c_1 \in \mathbb{R} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \text{d}_t z = \pm \sqrt{c_1 - \exp(z)} \end{align}

At first, it might seem that both signs need to be treated separately. However, it can actually be shown that both equations lead to the same solutions[1]. In the following, therefore, only the equation with a positive sign will be considered. To solve this, the following substitution is used:

\begin{align} z = \ln(y) \end{align}

This results in the following for the differential equation under consideration:

\begin{align} \frac{\text{d}_t y}{y} = \sqrt{c_1 - y} \end{align}

Separation of variables yields:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \frac{\text{d}y}{y\sqrt{c_1 - y}} = \text{d}t \\[6pt] \Rightarrow\;& \frac{1}{\sqrt{c_1}} \ln\left(\bigg|\frac{\sqrt{c_1 - y} - \sqrt{c_1}}{\sqrt{c_1 - y} + \sqrt{c_1}}\bigg|\right) = t + C_2 \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \bigg|\frac{\sqrt{c_1 - y} - \sqrt{c_1}}{\sqrt{c_1 - y} + \sqrt{c_1}}\bigg| = \exp\left(\sqrt{c_1} t + \sqrt{c_1} C_2\right) \, , \quad \text{with} \, c_2 = \exp\left(\sqrt{c_1} C_2\right) \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \bigg|\frac{\sqrt{c_1 - y} - \sqrt{c_1}}{\sqrt{c_1 - y} + \sqrt{c_1}}\bigg| = c_2 \exp\left(\sqrt{c_1} t\right) \, , \quad \text{with} \, A = c_2 \exp\left(\sqrt{c_1} t\right) \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \bigg|\frac{\sqrt{c_1 - y} - \sqrt{c_1}}{\sqrt{c_1 - y} + \sqrt{c_1}}\bigg| = A \, , \quad \text{with} \, y = \exp(z) \Rightarrow \sqrt{c_1 - y} > \sqrt{c_1} \; \forall y \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \frac{\sqrt{c_1} - \sqrt{c_1 - y}}{\sqrt{c_1} + \sqrt{c_1 - y}} = A \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& y = 4 c_1 \frac{A}{(1 + A)^2} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \exp(u) = \frac{4 c_1}{a \rho_0 r^2} \frac{A}{(1 + A)^2} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \rho = \frac{4 c_1 \rho_0}{a \rho_0 r^2} \frac{A}{(1 + A)^2} \end{align}

The quantity \(A\) can be written as follows:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& A = c_2 \exp\left(\sqrt{c_1} t\right) \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& A = c_2 \exp\left(\sqrt{2 c_1} \ln(\sqrt{a \rho_0} r)\right) \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& A = c_2 (\sqrt{a \rho_0} r)^{\sqrt{2 c_1}} \end{align}

Define additionally:

\begin{align} b := \sqrt{2 c_1} \quad \text{und} \quad r_0 := \left(c_2^\frac{1}{b} \sqrt{a \rho_0}\right)^{-1} \end{align}

This yields the following general solution for the differential equation under consideration:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \rho(r) = \frac{2 b^2}{a r^2} \frac{\left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^b} {\left(1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^b\right)^2} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \rho(r) = \frac{2 b^2}{a r_0^2} \frac{\left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^{b-2}} {\left(1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^b\right)^2} \end{align}

The integration constants \(r_0\) and \(b\) must then be determined using appropriate boundary conditions. For the problem considered, it makes sense to specify boundary conditions for the center of the cylinder, i.e., for \(r = 0\). In the considered case, the density at the center of the cylinder must be finite and nonzero, since both a vanishing and a diverging density at the origin would lead to unphysical behavior:

\begin{align} \rho(r=0) = \rho_c \, , \quad \text{with} \quad 0 < \rho_c < \infty \end{align}

Furthermore, rotational symmetry and the requirement for a smooth, regular solution imply that the density profile at the origin should not have a gradient. Consequently, \(\rho(r)\) has an extremum at \(r=0\), and the following applies:

\begin{align} \text{d}_r \rho(r) \big|_{r = 0} = 0 \end{align}

It should be noted that the substitution \(t=\sqrt{2}\ln\big(\sqrt{a\rho_0}r\big)\) is only defined for \(r>0\). The differential equation was thus initially solved in the domain \(r \in \mathbb{R}\). In order to formulate boundary conditions at \(r=0\), the solution must be extended continuously to \(r=0\). Accordingly, the central values are understood as right-sided limits:

\begin{align} \rho(r = 0) = \lim\limits_{r \rightarrow 0} \rho(r) \quad \text{and} \quad \text{d}_r \rho(r) \big|_{r = 0} = \lim\limits_{r \rightarrow 0} \text{d}_r \rho(r) \end{align}

With the first boundary condition, the following then applies:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \lim\limits_{r \rightarrow 0} \rho(r) = \rho_c \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \lim\limits_{r \rightarrow 0} \frac{2 b^2}{a r_0^2} \frac{\left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^{b-2}} {\left(1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^b\right)^2} = \rho_c \end{align}

Since the denominator converges to \(1\) in the limit case \(r\rightarrow 0\), the local behavior of the density in the immediate vicinity of the origin is determined exclusively by the numerator. This, together with the fact that the density at the origin must not vanish or diverge, directly implies that the following must hold:

\begin{align} b = 2 \end{align}

Inserting into the solution for the density profile provides:

\begin{align} \rho(r) = \frac{8}{a r_0^2} \frac{1} {\left(1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^2\right)^2} \end{align}

Furthermore, the first boundary condition implies that:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \rho_c = \frac{8}{a r_0^2} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& r_0^2 = \frac{8}{a \rho_c} \end{align}

Inserting this gives the stationary density profile of an infinitely long, isothermal, self-gravitating gas cylinder:

\begin{align} \rho(r) = \frac{\rho_c}{\left(1 + \frac{1}{8} a \rho_c r^2\right)^2} \end{align}

It is noticeable that the second boundary condition is not explicitly included in the determination of the integration constants \(r_0\) and \(b\). The reason for this is that the requirement for a finite central density different from zero already restricts the solution so much that only the case \(b=2\) remains. Thus, the density profile takes the above form and automatically satisfies the second boundary condition. It is therefore not redundant, but is already implicitly contained in the regularity and symmetry requirements.

In this context, the total mass per unit length \(\lambda_{\text{total}}\) of an infinitely long, isothermal gas cylinder held together by its own gravity can be introduced:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \lambda_{\text{total}} = 2 \pi \int_{0}^{\infty} \rho(r) r \text{d} r \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \lambda_{\text{total}} = \frac{8 \pi}{a} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \lambda_{\text{total}} = \frac{2 R T}{G M} \end{align}

The solution for the density profile can therefore also be written as follows:

\begin{align} \rho(r) = \frac{\lambda_{\text{total}}}{\pi r_0^2} \frac{1}{\left(1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^2\right)^2} \end{align}

With the determined density distribution, the gravitational potential induced by the density distribution can now be determined using Poisson's equation. The Poisson equation, using the given symmetry, is given by:

\begin{align} \frac{1}{r} \partial_r \left(r \partial_r \phi_\text{ext}(r)\right) = 4 \pi G \rho(r) \end{align}

Also here, due to the symmetry, the partial derivatives can be replaced by total derivatives:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \frac{1}{r} \text{d}_r \left(r \text{d}_r \phi_\text{ext}(r)\right) = 4 \pi G \rho(r) \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \text{d}_r \left(r \text{d}_r \phi_\text{ext}(r)\right) = 4 \pi G \rho(r) r \end{align}

Integration yields:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& r \text{d}_r \phi_\text{ext}(r) = 4 \pi G \int_{0}^{r} \rho(r^\prime) r^\prime \text{d} r \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& r \text{d}_r \phi_\text{ext}(r) = \frac{32 \pi G}{a r_0^2} \int_{0}^{r} \frac{r^\prime}{\left(1 + \left(\frac{r^\prime}{r_0}\right)^2\right)^2} \text{d} r \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& r \text{d}_r \phi_\text{ext}(r) = \frac{16 \pi G}{a} \frac{\left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^2} {1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^2} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \text{d}_r \phi_\text{ext}(r) = \frac{16 \pi G}{a r_0} \frac{\frac{r}{r_0}}{1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^2} \end{align}

Another integration yields the gravitational potential of of an infinitely long, isothermal, self-gravitating gas cylinder:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \phi_\text{ext}(r) = \frac{16 \pi G}{a r_0} \int_{0}^{r} \frac{\frac{r^\prime}{r_0}}{1 + \left(\frac{r^\prime}{r_0}\right)^2} \text{d} r \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \phi_\text{ext}(r) = \frac{8 \pi G}{a} \ln\left(1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^2\right) \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \phi_\text{ext}(r) = G \lambda_{\text{total}} \ln\left(1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^2\right) \end{align}

- ↑ Switching sign just flips the sign of \(b\), and the final \(\rho\) is invariant wrt \(b\to -b\).

The case with a core

We now consider an infinitely long cylinder with radius \(R_{\text{min}}\), surrounded by an isothermal gas that is held together by gravity from the core on the one hand and by its self-gravity on the other. It can be shown that this system follows the same differential equation for density distribution as the case without a core. The starting point here is also the hydrostatic Euler equation. For this, the external force density or force \(\text{d} \boldsymbol{F}_{\text{ext}}\) of the gas, including the core, is required on a mass element \(\rho(r) \text{d} V\), which is given by:

\begin{align} \text{d} \boldsymbol{F}_{\text{ext}} = - \frac{2 G \lambda(r) \rho(r) \text{d} V}{r} \boldsymbol{e}_r \, , \quad \text{mit} \quad r > R_{\text{min}} \end{align}

Here, \(\lambda(r)\) is the mass per unit length enclosed up to radius \(r\). It is given by:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \lambda(r) = 2 \pi \int_{0}^{r} \rho(r^\prime) r^\prime \text{d} r^\prime \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \lambda(r) = \lambda_{\text{core}} + 2 \pi \int_{R_{\text{min}}}^{r} \rho(r^\prime) r^\prime \text{d} r^\prime \end{align}

Here, \(\lambda_{\text{core}}\) is the mass per unit length of the core. Substituting this into the hydrostatic Euler equation gives:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \boldsymbol{\nabla} P = - \frac{2 G \rho}{r} \left(\lambda_{\text{core}} + 2 \pi \int_{R_{\text{min}}}^{r} \rho(r^\prime) r^\prime \text{d} r^\prime\right) \boldsymbol{e}_r \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \frac{R T}{M} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \rho = - \frac{2 G \rho}{r} \left(\lambda_{\text{core}} + 2 \pi \int_{R_{\text{min}}}^{r} \rho(r^\prime) r^\prime \text{d} r^\prime\right) \boldsymbol{e}_r \end{align}

Due to the given cylinder symmetry, the following then applies:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \frac{R T}{M} \text{d}_r \rho = - \frac{2 G \rho}{r} \left(\lambda_{\text{core}} + 2 \pi \int_{R_{\text{min}}}^{r} \rho(r^\prime) r^\prime \text{d} r^\prime\right) \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \frac{R T}{2 G M} \frac{r \text{d}_r \rho}{\rho} = - \left(\lambda_{\text{core}} + 2 \pi \int_{R_{\text{min}}}^{r} \rho(r^\prime) r^\prime \text{d} r^\prime\right) \end{align}

Differentiating with respect to \(r\) then yields:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \frac{R T}{2 G M} \text{d}_r \left(\frac{r \text{d}_r \rho}{\rho}\right) = - 2 \pi \rho r \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \frac{\text{d}_r \rho}{\rho} - r \left(\frac{\text{d}_r \rho}{\rho}\right)^2 + r \frac{\text{d}_r^2 \rho}{\rho} = - a r \rho \end{align}

Therefore, the general solution of the system under consideration is given by the general solution of the system without the core:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \rho(r) = \frac{2 b^2}{a r_0^2} \frac{\left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^{b-2}} {\left(1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^b\right)^2} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \rho(r) = \frac{b^2 \lambda_{\text{total}}}{4 \pi r_0^2} \frac{\left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^{b-2}} {\left(1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^b\right)^2} \end{align}

A condition for the existence of physically meaningful density profiles can be derived from Euler's hydrostatic equation. Under the assumed symmetry, the following then applies:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \frac{R T}{M} \text{d}_r \rho = - \frac{2 G \lambda \rho}{r} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \frac{R T}{M} \text{d}_r \ln(\rho) = - \frac{2 G \lambda}{r} \end{align}

Applying the general solution and then performing the derivations yields:

\begin{align} \frac{R T}{M} \left(\frac{b - 2}{r} - \frac{2 b}{r} \frac{\left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^b}{1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^b}\right) = - \frac{2 G \lambda}{r} \end{align}

Since this equation holds for all \(r \in \mathbb{R}_{> 0}\), it must be satisfied in particular on the surface of the core. With \(\lambda(r = R_{\text{min}}) = \lambda_{\text{core}}\), the following then follows:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \frac{R T}{M} \left(\frac{b - 2}{R_{\text{min}}} - \frac{2 b}{R_{\text{min}}} \frac{\left(\frac{R_{\text{min}}}{r_0}\right)^b}{1 + \left(\frac{R_{\text{min}}}{r_0}\right)^b}\right) = - \frac{2 G \lambda_{\text{core}}}{R_{\text{min}}} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \frac{r_0}{R_{\text{min}}} = \left(\frac{b + 2 - 4 \frac{\lambda_{\text{core}}}{\lambda_{\text{total}}}} {b - 2 + 4 \frac{\lambda_{\text{core}}}{\lambda_{\text{total}}}}\right)^{\frac{1}{b}} \end{align}

Since the left side of the equation is non-negative by definition, it follows that for the exponent \(b\), the following must apply:

\begin{align} b > \biggl|4 \frac{\lambda_{\text{core}}}{\lambda_{\text{total}}} - 2\biggr| \end{align}

The gas mass per unit length \(\lambda_{\text{gas}}\) can then be expressed in terms of the mass per unit length of the core and the exponent. The gas mass per unit length is generally given by:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \lambda_{\text{gas}} = 2 \pi \int_{R_{\text{min}}}^{\infty} \rho(r) r \text{d} r \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \lambda_{\text{gas}} = \frac{b^2 \lambda_{\text{total}}}{2 r_0^b} \int_{R_{\text{min}}}^{\infty} \frac{r^{b-1}} {\left(1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^b\right)^2} \text{d} r \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \lambda_{\text{gas}} = \frac{b \lambda_{\text{total}}}{2} \frac{1}{1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^b} \end{align}

Using the expression for \(\frac{r_0}{R_{\text{min}}}\) derived above, it follows:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \lambda_{\text{gas}} = \frac{b + 2}{4} \lambda_{\text{total}} - \lambda_{\text{core}} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \frac{\lambda_{\text{gas}} + \lambda_{\text{core}}}{\lambda_{\text{total}}} = \frac{b + 2}{4} \end{align}

If the core is a numerical necessity, it is only there to emulate the gas within the core radius. Therefore, the case \(b = 2\) continues to be considered for this case. For this case, the core mass per unit length must be selected as follows, for a given core radius:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \lambda_{\text{core}} = 2 \pi \int_{0}^{R_{\text{min}}} \rho(r,b=2) r \text{d} r \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \lambda_{\text{core}} = \frac{2 \lambda_{\text{total}}}{r_0^2} \int_{0}^{R_{\text{min}}} \frac{r}{\left(1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^2\right)^2} \text{d} r \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \lambda_{\text{core}} = \frac{R_{\text{min}}^2} {R_{\text{min}}^2 + r_0^2}\lambda_{\text{total}} \end{align}

This results in the following for the gas mass per unit length in the system:

\begin{align} \lambda_{\text{gas}} = \frac{r_0^2} {R_{\text{min}}^2 + r_0^2}\lambda_{\text{total}} \end{align}

The case with a core (Lothar)

The solution to the ODE reads

\begin{align} \rho &= \frac{\lambda b^2(r/r_0)^{b-2}}{4\pi r_0^2(1+(r/r_0)^b)^2}\\[2ex] \text{with}\quad \lambda &= \frac{2k_\text{B}T}{Gm} = \int_0^\infty 2\pi r\rho(r,r_0,b{=}2)\,\text dr \end{align} being the only possible total mass/length in the case of gas only, where \(b=2\) is necessary for zero force at \(r=0\). Notably, \(\lambda\) does not depend on \(r_0\), i.e. every width of \(\rho\) is equally allowed. The reason is that no length scale can be constructed from the input parameters \(k_\text{B}T\), \(G\) and \(m\).

This changes in the presence of a core with mass/length \(\lambda_\text{c}\) and radius \(R\). Vanishing force at \(r=0\) is replaced by force balance at \(r=R\), which leads to the condition \begin{align} \frac{r_0}{R} &= \left(\frac{b+2-4\lambda_\text{c}/\lambda}{b-2+4\lambda_\text{c}/\lambda}\right)^{1/b} ~, \end{align} which in turn introduces the constraint \(b>\vert 4\lambda_\text{c}/\lambda-2\vert\).

The resulting gas mass is \begin{gather} \int_R^\infty 2\pi r\rho(r,r_0,b)\,\text dr = \lambda\frac{b+2}{4}-\lambda_\text{c}\\ \Leftrightarrow\quad \frac{\lambda_\text{c}+\lambda_\text{gas}}{\lambda}=\frac{b+2}{4} ~. \end{gather} That is, the amount of gas can be tuned via \(b\). Note that for \(\lambda_\text{c}<\lambda/2\), it cannot be chosen arbitrarily small.

If the core is actually a numerical necessity and only meant to emulate the gas contained inside, it's \(b=2\) again, and the most convenient choice is \(\lambda_\text{c}=\lambda_\text{gas}=\lambda/2\) which yields \(r_0=R\).

Free-fall time of an Ostriker cylinder

Sought is the free fall time \(t_{\text{ff}}\) of an infinitely long, isothermal gas cylinder that is initially at rest and has the following density profile:

\begin{align} \rho(r) = \frac{\lambda_{\text{total}}}{\pi r_0^2} \frac{1}{\left(1 + \left(\frac{r}{r_0}\right)^2\right)^2} \end{align}

To determine the free fall time, an infinitesimal cylindrical shell with radius \(r_{\text{i}}\) and mass \(\rho(r_i) \text{d} V\) is considered, whose gas, according to Newton's shell theorem, is gravitationally accelerated radially inwards by the mass enclosed by the cylindrical shell. Due to symmetry, the problem is reduced to a one-dimensional, purely radial motion. The equation of motion to be solved is therefore:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \rho(r_{\text{i}}) \text{d} V \frac{\text{d}^2 r}{\text{d} t^2} = - \frac{2 G \lambda(r_{\text{i}}) \rho(r_{\text{i}}) \text{d} V}{r} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \frac{\text{d}^2 r}{\text{d} t^2} = - \frac{2 G \lambda(r_{\text{i}})}{r} \end{align}

Here, \(\lambda(r_{\text{i}})\) is the mass enclosed by the cylinder shell per unit length, which is given by the following equation for the given density distribution:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \lambda(r_{\text{i}}) = 2 \pi \int_{0}^{r_{\text{i}}} \rho(r) r \text{d} r \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \lambda(r_{\text{i}}) = \frac{r_{\text{i}}^2} {r_{\text{i}}^2 + r_0^2}\lambda_{\text{total}} \end{align}

Inserting yields:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \frac{\text{d}^2 r}{\text{d} t^2} = - \frac{2 G \lambda_{\text{total}}}{r} \frac{r_{\text{i}}^2}{r_{\text{i}}^2 + r_0^2} \, , \quad \text{def.:} \, K := 2 G \lambda_{\text{total}} \frac{r_{\text{i}}^2}{r_{\text{i}}^2 + r_0^2} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \frac{\text{d}^2 r}{\text{d} t^2} = - \frac{K}{r} \, , \quad \text{with} \ v = \frac{\text{d} r}{\text{d} t} \, , \, \frac{\text{d} v}{\text{d} t} = v \frac{\text{d} v}{\text{d} r} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& v \frac{\text{d} v}{\text{d} r} = - \frac{K}{r} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& v \text{d} v = - \frac{K}{r} \text{d} r \\[6pt] \Rightarrow\;& \frac{1}{2}v^2 = - K \ln(r) + C \end{align}

From the initial conditions \(r(t=0) = r_{\text{i}}\) and \(v(t=0) = 0\), the following applies to the integration constant:

\begin{align} C = K \ln(r_i) \end{align}

Thus follows:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \frac{1}{2}v^2 = - K \ln\left(\frac{r_{\text{i}}}{r}\right) \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& v = \pm \sqrt{2 K \ln\left(\frac{r_{\text{i}}}{r}\right)} \end{align}

Since the collapse is directed inwards, only the negative branch of the solution for the velocity is relevant, which is why only this branch will be considered in the following:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& v = - \sqrt{2 K \ln\left(\frac{r_{\text{i}}}{r}\right)} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \frac{\text{d} r}{\text{d} t} = - \sqrt{2 K \ln\left(\frac{r_{\text{i}}}{r}\right)} \\[6pt] \Rightarrow\;& \int_{0}^{t_{\text{ff}}} \text{d} t = - \int_{r_{\text{i}}}^{0} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 K \ln\left(\frac{r_{\text{i}}}{r}\right)}} \text{d} r \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& t_{\text{ff}} = \sqrt{\frac{\pi}{2 K}} r_{\text{i}} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& t_{\text{ff}} = \frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2} \sqrt{\frac{r_{\text{i}}^2 + r_0^2}{G \lambda_{\text{total}}}} \end{align}

Work Plan and Approach

The following section presents a rough work plan for this master's thesis, which aims to numerically reproduce the solutions developed by Fiege and Pudritz. The initial goal is to simulate the purely hydrostatic reference case, the infinitely long, isothermal, self-gravitating cylinder without magnetic fields, in PLUTO/belt. Due to the cylindrical symmetry, the first tests can be carried out in a one-dimensional setup in cylindrical coordinates.

Afterwards, the numerical setup will be gradually expanded to two and then three dimensions. Once the three-dimensional setup in cylindrical coordinates is stable and works reliably, the plan is to switch to a three-dimensional setup in Cartesian coordinates. Cartesian coordinates are needed for the considered problem because the instabilities to be investigated later are expected to break the cylindrical symmetry.

Once the three-dimensional setup is in Cartesian coordinates, the next step will be to extend it to magnetohydrodynamic calculations. The aim here is to implement the equilibrium solutions of Fiege and Pudritz (2000a) in PLUTO/belt. Finally, the equilibrium configuration should be disturbed, analogous to Fiege and Pudritz (2000b), in order to investigate the temporal development of the perturbations and compare them with the predictions of their linear stability analysis.

1D Hydrodynamic Reference Test: Setup and Convergence

As explained above, the study starts with purely hydrodynamic, one-dimensional, isothermal simulations including self-gravity. The simulation setup is initialised according to an infinitely long, isothermal, self-gravitating cylinder with a core. Specifically, the density profile is set according to the previously derived density distribution, the velocity field is initialised to zero at the start, and the core mass is selected according to the relation given above. The temperature \(T\) and the characteristic radius \(r_0\) are selected based on typical values for observed filaments (cf. Seifried and Walch, 2015):

\begin{align} T = 10 \, \text{K} \quad \text{and} \quad r_0 = 0.033 \, \text{pc} \end{align}

For the initial simulations, a grid extending from \(r = 10^{-4}\,\text{pc}\) to \(r = 1\,\text{pc}\) is used. This ensures that the numerical domain completely encompasses the filament and that the outer region is sufficiently large to minimise boundary artefacts.

The grid is designed so that the cells become linearly larger towards the outside. This ensures high resolution in the area of interest, i.e. in and around the filament, especially near the core, while a coarser resolution is sufficient further out, where in the case under consideration there are typically only very low densities or the filament transitions into an almost vacuum state. This achieves a good balance between accuracy in the relevant region and the highest possible numerical efficiency.

For the hydrodynamic variables, reflective boundary conditions are used at the inner edge of the domain. This is because the inner edge represents an impenetrable core and the reflective boundary condition prevents mass flow across the boundary surface. For the outer boundary, outflow–no-inflow boundary conditions are selected in order to model the domain as an open system. This allows matter, disturbances and waves to leave the domain, while preventing inflow from outside.

For the gravitational potential of the gas in the domain, a zero-gradient boundary condition is used at the inner edge. The reason for this is that the gravitational attraction of the core is considered separately in PLUTO/belt. Since gravitational potentials can be superimposed due to the linearity of Poisson's equation, the potential generated by the gas can then be linearly added to the potential generated by the core. At the outer boundary, the potential is specified by the analytical potential solution for an infinitely long, isothermal, self-gravitating cylinder without a core. This boundary condition is permissible in this setup because the core serves only as a numerical aid to emulate the case without a core.

The first simulation with this setup was performed with \(N_r = 1000\) cells in the radial direction. As a result, it can be seen that the maximum density in the system, which corresponds to the density in the innermost cell at the core due to the selected density profile, initially undergoes a damped oscillation. The maximum density then stabilises at a value of approximately \(\rho_{\max} = 3.26 \cdot 10^{-19}\,\frac{\text{g}}{\text{cm}^3}\). This corresponds to an upward deviation of about \(3\,\%\) from the initial and thus analytically expected value. This behaviour is illustrated in the following figure:

Due to conservation of mass, the increase in maximum density causes the density distribution to contract slightly. This is evident in the fact that the density peak increases while the characteristic radius decreases. As a result, the profile becomes narrower overall and more concentrated towards the centre. This behaviour is illustrated in the following figure, which shows the radial density distribution of the converged simulation and the theoretically expected density distribution used as the initial condition:

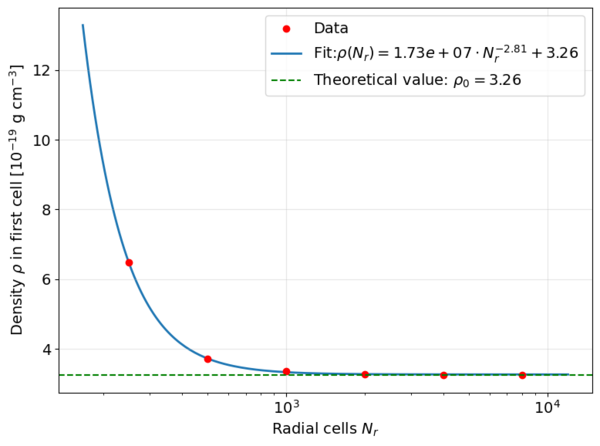

Here, it can be seen that the density peak deviates upwards by approximately \(3\,\%\). This contraction of the density distribution becomes significantly weaker at higher resolutions, as can be seen in the following figure. There, the density in the innermost cell, i.e. in the first cell at the core, is shown as a function of the number of cells \(N_r\) used:

Here, it can be seen that the density in the innermost cell converges towards the theoretically expected value as the number of cells increases. For \(N_r = 8000\), the maximum density deviates upwards by only about \(0.0002\,\%\). In addition, no damped oscillation is longer visible in the temporal development of the maximum density. Instead, there is a monotonic increase towards the equilibrium value, which qualitatively corresponds to overdamped behaviour. This behaviour is shown in the following figure. The left plot shows the density in the innermost cell as a function of time, and the right plot shows the radial density distribution of the converged simulation as well as the theoretically expected density distribution used as the initial condition.