Planetesimal-Erosion: Difference between revisions

(Numerical Methods) |

|||

| (9 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 328: | Line 328: | ||

\begin{align} | \begin{align} | ||

\phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& | \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& | ||

\mu_{\infty}^* = \frac{\mu_{\infty}}{\rho_{\infty} u_{\infty} R} \; , \quad \mu_{\infty} = \frac{\rho_{\infty} u_{\infty} R}{\text{Re}_{\infty}} | \mu_{\infty}^* = \frac{\mu_{\infty}}{\rho_{\infty} u_{\infty} R} \; , \quad | ||

\mu_{\infty} = \frac{2\rho_{\infty} u_{\infty} R}{\text{Re}_{\infty}} | |||

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

\Leftrightarrow\;& | \Leftrightarrow\;& | ||

\mu_{\infty}^* = \frac{ | \mu_{\infty}^* = \frac{2}{\text{Re}_{\infty}} | ||

\end{align} | \end{align} | ||

| Line 337: | Line 338: | ||

\begin{align} | \begin{align} | ||

&\sigma^*\Big|_{r^*=1} = - p^*\Big|_{r^*=1} + \frac{ | &\sigma^*\Big|_{r^*=1} = - p^*\Big|_{r^*=1} + \frac{8}{3\text{Re}_{\infty}} | ||

\frac{\partial u_r^*}{\partial r^*}\Big|_{r^*=1} | \frac{\partial u_r^*}{\partial r^*}\Big|_{r^*=1} | ||

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

&\tau^*\Big|_{r^*=1} = | &\tau^*\Big|_{r^*=1} = | ||

\frac{ | \frac{2}{\text{Re}_{\infty}}\bigg|\frac{\partial u_\theta^*}{\partial r^*}\Big|_{r^*=1}\bigg| | ||

\end{align} | \end{align} | ||

| Line 356: | Line 357: | ||

== Computational domain == | == Computational domain == | ||

As explained a sphere with the radius \(R\) around which a viscous fluid flows with an inflow velocity \(\boldsymbol{u}=-u_{\infty}\boldsymbol{e}_z\) is investigated. Due to the spherical symmetry of the problem, the computational domain is modelled in spherical coordinates, with the centre of the sphere at the origin of the coordinate system. However, due to the axial symmetry, it is sufficient to set up a two-dimensional simulation domain, whereby only the radial component \(r\) and the polar component \(\theta\) are considered. | As explained a sphere with the radius \(R\) around which a viscous fluid flows with an inflow velocity \(\boldsymbol{u}_{\infty}=-u_{\infty}\boldsymbol{e}_z\) is investigated. Due to the spherical symmetry of the problem, the computational domain is modelled in spherical coordinates, with the centre of the sphere at the origin of the coordinate system. However, due to the axial symmetry, it is sufficient to set up a two-dimensional simulation domain, whereby only the radial component \(r\) and the polar component \(\theta\) are considered. | ||

The grid extends from an inner radius \(R_{\text{I}}\), which corresponds to the spherical radius \(R\), to an outer radius \(R_{\text{A}}\). In the polar direction, the grid starts at an angle of \(\theta_\text{S}=0\) and extends to \(\theta_{\text{E}}=\pi\). The number of cells \(N_r\) in the radial direction and \(N_\theta\) in the polar direction is selected so that the cells have an approximately square shape. This configuration is crucial for the numerical precision of the simulations, as highly distorted cells are more susceptible to numerical errors. | The grid extends from an inner radius \(R_{\text{I}}\), which corresponds to the spherical radius \(R\), to an outer radius \(R_{\text{A}}\). In the polar direction, the grid starts at an angle of \(\theta_\text{S}=0\) and extends to \(\theta_{\text{E}}=\pi\). The number of cells \(N_r\) in the radial direction and \(N_\theta\) in the polar direction is selected so that the cells have an approximately square shape. This configuration is crucial for the numerical precision of the simulations, as highly distorted cells are more susceptible to numerical errors. | ||

| Line 366: | Line 367: | ||

\big(10^{\Delta\xi}-1\big) | \big(10^{\Delta\xi}-1\big) | ||

\end{align} | \end{align} | ||

Where \(r_{i-\frac{1}{2}}\) is the distance from the origin to the cell wall of the \(i\)-th cell closer to the sphere. In addition, \(\Delta\xi\) is given by: | |||

\begin{align} | |||

\Delta\xi | |||

=\frac{1}{N_r}\log_{10} | |||

\bigg(\frac{R_A}{R}\bigg) | |||

\end{align} | |||

In the polar direction, the grid cells in this project have a uniform angular size \(\Delta\theta\). Due to the fact that the length of a cell in the polar direction is given by \(r_i\cdot\Delta\theta\), the length of the cells in the polar direction grows radially outwards to the same extent as the length of the cells in the radial direction \(\Delta r_i\). With a fixed radius \(r_j\), however, the grid cells in the polar direction have the same length \(r_j\cdot\Delta\theta\). The angular size \(\Delta\theta\) results from the quotient of the difference between the start and end angle of the defined grid and the number of cells in the polar direction. The following therefore applies: | |||

\begin{align} | |||

\Delta\theta=\frac{\pi}{N_\theta} | |||

\end{align} | |||

As already mentioned, the simulation grid represents the area surrounding the sphere under consideration, but not the sphere itself. In order to simulate the problem of the flowing sphere, appropriate boundary conditions must be specified for the system. In this setup, the system is supplied with the so-called reflective boundary condition at the grid’s inner radius. A more detailed explanation of this type of boundary condition can be found in the [https://plutocode.ph.unito.it/userguide.pdf PLUTO User's Guide]. At the outer radius, the corresponding fields are set to the specified values at infinity. The following applies then: | |||

\begin{align} | |||

&\rho(R_A)=\rho_\infty | |||

\\[6pt] | |||

&p(R_A)=p_\infty | |||

\\[6pt] | |||

&\boldsymbol{u}(R_A)=\boldsymbol{u}_{\infty} | |||

\end{align} | |||

Due to the fact that a two-dimensional computational domain is considered because of the axial symmetry of the system, the computational domain has the shape of a half disc with a hole in the origin, of diameter \(2R\). Therefore, boundary conditions must also be specified for the axes \((r,\theta=0)\) and \((r,\theta=\pi)\). The so-called axissymmetric boundary condition is applied there. This boundary condition ensures axial symmetry in the simulations. A more detailed explanation of this type of boundary condition can also be found in the [https://plutocode.ph.unito.it/userguide.pdf PLUTO User's Guide]. | |||

== Numerical calculation of the stresses == | |||

As PLUTO only outputs the data for the respective cell centres, the pressure and velocity fields in particular are not output on the surface of the sphere. However, these fields are required to calculate the stresses acting on the sphere. | |||

The velocity field on the surface of the sphere is already determined by the boundary conditions. However, the pressure on the surface of the sphere is unknown and must therefore be extrapolated. Linear extrapolation is suitable here, as it has a second-order error which corresponds to the errors of the methods used to determine the derivatives of the fields. For the linear extrapolation of the pressure on the spherical surface \(p(r=R)=p_0\), the next two data points \((r_1,p_1)\) and \((r_2,p_2)\) are required. The extrapolated pressure is then given by: | |||

\begin{align} | |||

p_0=p_2+\frac{R-r_2}{r_1-r_2}(p_1-p_2) | |||

\end{align} | |||

The derivatives are determined numerically using the Numpy function <code>numpy.gradient</code>. This function can approximate derivatives of functions defined by discrete data points and has a second-order error. A key advantage of this function is its ability to calculate derivatives with inhomogeneous step sizes \(\Delta r_i\). This property is of particular importance in the context of this project, as the cell size in the simulation grid under consideration increases linearly in the radial direction. Correspondingly, the distances between the output data points and thus the step sizes also increase linearly. | |||

For the present investigation, mainly derivatives at the inner edge of the simulation area are required. By default, <code>numpy.gradient</code> uses one-sided first-order differences at the edges, which results in a first-order error there. By setting the parameter <code>edge_order=2</code>, one-sided second-order differences are used instead, so that a second-order error is also guaranteed at the boundary points. A detailed explanation of the exact calculation of the derivatives can be found in the [https://numpy.org/doc/2.1/reference/generated/numpy.gradient.html Numpy documentation]. | |||

This means that the stresses for each cell in the simulation area, and in particular at its inner edge, can now be determined with second-order accuracy. | |||

= Results and discussion = | |||

Before the simulations for tuning the Mach numbers can be carried out, a suitable setup must first be found. This setup should be chosen in such a way that, on the one hand, the results are not distorted by the choice of setup and, on the other hand, the simulation duration remains within reasonable limits. | |||

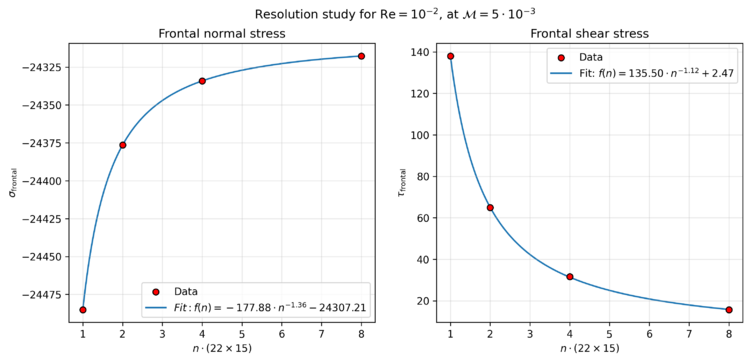

== Resolution study == | |||

It is to be expected that the simulation data and, accordingly, the results for very coarse grids may be distorted due to the discretisation of the space. It is therefore advisable to first carry out several simulations for grids with different resolutions. The aim is to find the coarsest grid for which the relevant quantities, such as normal stress and shear stress, no longer change or change only slightly. For this purpose, parameters such as the Mach number and the Reynolds number are kept constant in the corresponding simulations. | |||

First, the parameters are selected in line with the bachelor's thesis ([https://wiki.uni-due.de/agk/index.php?title=BA_Emilio_Schmidt Emilio Schmidt, 2024]). Specifically, a Mach number of \(\mathcal{M} = 5 \cdot 10^{-3}\) and a Reynolds number of \(\text{Re} = 10^{-2}\) are selected. This choice serves to verify whether the transition to the new system of natural units has been consistent. In particular, it should be ensured that the relevant quantities also converge in this system of units with increasing resolution. | |||

For the first simulation of this resolution study, a grid was selected whose inner radius \(R_I/R=1\) corresponds to the radius of the sphere being flowed upon in the selected natural units and whose outer radius is \(R_A/R=100\). The grid initially contains \(22\) cells in the radial direction, which increase linearly with the outer radius. In the polar direction, there are \(15\) cells of uniform size. In the following simulations, the number of cells in the radial and polar directions is multiplied by a natural number \(n\in\mathbb{N}\). This results in a cell count of \(n\cdot 22\) in the radial direction and \(n\cdot 15\) in the polar direction. In the following, such a grid is referred to as a grid with resolution \(n\). | |||

The following figure shows both the frontal normal stress, i.e. the normal stress acting on the sphere in the direction of flow, and the frontal shear stress across the grid resolution, including a power law fit: | |||

[[File:Resolution study.png|750px|thumb|center|Resolution study for a Reynolds number of \(\text{Re} = 10^{-2}\) and a Mach number of \(\mathcal{M} = 5 \cdot 10^{-3}\). The values of the frontal normal stress (left) and the frontal shear stress (right) are shown as a function of the grid resolution \(n\). Both variables were additionally fitted with a power law. The results show that both normal and shear stress converge with increasing resolution.]] | |||

The figure shows that the two quantities converge as the resolution increases. This confirms that the transition to the new system of natural units has been consistent. | |||

In the next step, an analogue resolution study is carried out, but for Reynolds numbers as used in [https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/ac1e88/meta Cedenblad et al. (2021)]. The same grid and Mach number are used, but the Reynolds number is now set to \(\text{Re} = 10^{3}\) instead of \(\text{Re} = 10^{-2}\). | |||

The following figure shows both the frontal normal stress and the frontal shear stress across the grid resolution, including the power law fit: | |||

[[File:Resolution study RE1E+3.png|750px|thumb|center|Resolution study for a Reynolds number of \(\text{Re} = 10^{3}\) and a Mach number of \(\mathcal{M} = 5 \cdot 10^{-3}\). The values of the frontal normal stress (left) and the frontal shear stress (right) are shown as a function of the grid resolution. Both variables were additionally fitted with a power law. The results show that both normal and shear stress converge with increasing resolution.]] | |||

The figure shows that both quantities converge with increasing grid resolution even at an elevated Reynolds number of \(\text{Re} = 10^{3}\). However, it is noticeable that convergence is significantly slower than in the case of the smaller Reynolds number \(\text{Re} = 10^{-2}\). In addition, the frontal normal stress exhibits different behaviour. While it decreases or increases in magnitude with increasing resolution at \(\text{Re} = 10^{3}\), it behaves in the opposite manner in the case of \(\text{Re} = 10^{-2}\), increasing or decreasing in magnitude with increasing resolution. | |||

The slow convergence can be explained by the behaviour of the boundary layer thickness \(\delta\), which generally scales with the Reynolds number for both laminar and turbulent flows as follows (see [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boundary_layer_thickness Wikipedia/Boundary_layer_thickness]): | |||

\begin{align} | |||

\delta \propto \text{Re}^{-a}, \quad a \in (0,1). | |||

\end{align} | |||

The exponent \(a\) takes on different values in the interval \((0,1)\) depending on the flow regime, but this is not relevant to the present argument. The decisive factor is that the boundary layer thickness decreases with increasing Reynolds number. Since the distributions of density, pressure and velocity within the boundary layer contribute significantly to the calculation of the stresses under consideration, this must be resolved numerically with sufficient accuracy. Consequently, higher Reynolds numbers require a correspondingly higher grid resolution in order to adequately represent the thinner boundary layer. | |||

The different convergence behaviour can be explained by the fact that the viscosity term, or more precisely the shear viscosity term, scales inversely with the Reynolds number in the normal stress in the selected system of natural units. For large Reynolds numbers, this term is negligible, so that the normal stress on the sphere surface is essentially determined by the negative pressure. As the resolution increases, the cell centres of the cells surrounding the particle move closer to the sphere surface, reducing the error in pressure extrapolation. At coarse resolutions, the pressure is systematically underestimated because the extrapolation is performed from cell centres that are further away from the surface. At low Reynolds numbers, however, the viscosity term cannot be neglected, but rather becomes dominant. Since the fluid is slowed down when it hits the sphere, the radial derivative of the radial velocity component on the sphere surface is positive and thus contributes positively to the normal stress. This derivative increases with increasing resolution for the same reason that the pressure increases at high Reynolds numbers. The cell centres closer to the surface provide more accurate values. Due to the dominance of the viscosity term, this contribution outweighs the increase in pressure, so that the normal stress increases with increasing resolution at low Reynolds numbers or decreases in magnitude. | |||

To be continued... | |||

Latest revision as of 10:37, 25 September 2025

Flow around a planetesimal

This project aims to investigate the flow around and erosion of a planetisimal by a viscous fluid under physical conditions that typically occur in protoplanetary discs. As a starting point, the erosion model presented in Cedenblad et al. (2021) will be numerically reproduced and systematically extended in perspective.

A first step is to investigate the stresses acting on the surface of a stationary sphere flown around by a gas. In particular, the influence of the Mach number in the range \(0<\mathcal{M}<2\) on the shear and normal stress distribution is to be investigated in order to gain a basic understanding of the flow conditions relevant for erosion.

Theoretical Framework

Required is the distribution of normal and shear stresses acting on the surface of a sphere at rest with radius \(R\) as a function of the Mach number \(\mathcal{M}\). The Mach number is defined as the ratio between the velocity \(\boldsymbol{u}\) of the flowing fluid (or an object moving through the fluid, depending on the chosen reference system) and the speed of sound \(c_\mathrm{S}\) of the considered medium:

\begin{align} \mathcal{M} = \frac{|\boldsymbol{u}|}{c_\mathrm{S}} \end{align}

The normal stress describes the component of the mechanical stress acting perpendicular to the surface and contains in particular the contribution of the static pressure. Shear stress, on the other hand, acts tangentially to the surface and is closely linked to velocity gradients in the fluid. Both quantities are components of the stress tensor \(\boldsymbol{\sigma}\) and play a central role in the description of force transmissions between fluid and body, especially with regard to possible erosion processes on the object surface.

Normal and shear stress

In fluid mechanics, the mechanical stress acting on a surface element is described by the stress tensor \(\boldsymbol{\hat\sigma}\). It specifies the internal stresses acting at each point of a continuum due to external forces. The stress tensor is a second-rank tensor whose components \(\sigma_{ij}\) represent the stresses acting on a surface with a normal in the direction of the \(j\)-th coordinate axis due to forces in the direction of the \(i\)-th coordinate axis. The stress tensor describes both the normal stress \(\sigma\) and the shear stress \(\tau\) acting on a surface element with unit normal vector \(\boldsymbol{n}\).

The mechanical stress that a fluid exerts on a certain surface within the continuum is described by the so-called traction vector \(\boldsymbol{T}\). This specifies the force per unit area that acts on a surface with a unit normal vector \(\boldsymbol{n}\). Mathematically, the traction vector results from the transpose of the application of the transposed normal vector to the stress tensor:

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{T} = \boldsymbol{n} \cdot \boldsymbol{\hat\sigma} \end{align}

The normal stress is the projection of this traction vector onto the normal coordinate axis:

\begin{align} \sigma = \boldsymbol{T} \cdot \boldsymbol{n}= (\boldsymbol{n} \cdot \boldsymbol{\hat\sigma}) \cdot \boldsymbol{n} \end{align}

In component-wise notation this results in:

\begin{align} \sigma = T_j \, n_j = \sigma_{ij} \, n_i \, n_j \end{align}

The shear stress corresponds to the magnitude of the shear stress vector \(\boldsymbol{\tau}\), which results from the subtraction of the normal stress vector \(\boldsymbol{\sigma}=\sigma\boldsymbol{n}\) from the traction vector: \begin{align} \boldsymbol{\tau} = \boldsymbol{T} - \sigma\boldsymbol{n} \end{align}

In component-wise notation this results in:

\begin{align} \tau_{\mathrm{n},j} = T_j - \sigma_{\mathrm{n}} \, n_j = \sigma_{ij} \, n_i - (\sigma_{kl} \, n_k \, n_l) \, n_j \end{align}

The shear stress is then given by :

\begin{align}

\phantom{\Rightarrow}\;&

\tau^2 =

|\boldsymbol{\tau}|^2 =

\tau_j \, \tau_j

\\[6pt]

\Leftrightarrow\;&

\tau^2 =

(\sigma_{ij} \, n_i - \sigma \, n_j)

(\sigma_{mj} \, n_m - \sigma \, n_j)

\\[6pt]

\Leftrightarrow\;&

\tau^2 =

\sigma_{ij} \, \sigma_{mj} \, n_i \, n_m -

\sigma_{ij} \, \sigma \, n_i \, n_j -

\sigma_{mj} \, \sigma \, n_m \, n_j +

\sigma^2

\\[6pt]

\Leftrightarrow\;&

\tau^2 =

(\sigma_{ij} \, n_i) (\sigma_{mj} \, n_m) -

(\sigma_{ij} \, n_i \, n_j) \, \sigma -

(\sigma_{mj} \, n_m \, n_j) \, \sigma +

\sigma^2

\\[6pt]

\Leftrightarrow\;&

\tau^2 =

T_j \, T_j - \sigma^2

\\[6pt]

\Leftrightarrow\;&

\tau^2 = \boldsymbol{T}^2 - \boldsymbol{\sigma}^2

\\[6pt]

\Rightarrow\;&

\tau =

\sqrt{

\boldsymbol{T}^2 - \boldsymbol{\sigma}^2

}

\end{align}

Normal and shear stresses on a sphere in a subsonic to slightly supersonic flow

The aim is now to determine the normal and shear stresses on the surface of the sphere. Since it is a sphere with centre at the origin, the unit normal vector at each point of the surface is identical to the unit vector in radial direction \(\boldsymbol{e}_r\):

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{n} = \boldsymbol{e}_r \end{align}

The traction vector on the surface of the sphere is therefore as follows:

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{T} = \boldsymbol{e}_r \cdot \boldsymbol{\hat\sigma} = \sigma_{rr} \boldsymbol{e}_r + \sigma_{r\theta} \boldsymbol{e}_\theta + \sigma_{r\varphi} \boldsymbol{e}_\varphi \end{align}

Die Normal- bzw.~ Scherspannung sind dann gegeben durch:

\begin{align} &\sigma = \boldsymbol{T} \cdot \boldsymbol{e}_r = \sigma_{rr} \\[6pt] &\tau_{\mathrm{n}} = \sqrt{ \boldsymbol{T}^2 - \boldsymbol{\sigma}^2 } = \sqrt{ \sigma_{r\theta}^2 + \sigma_{r\varphi}^2 } \end{align}

To explicitly determine the normal and shear stresses acting on the spherical surface, the stress tensor of the surrounding fluid is now required. This is generally given in a fluid by:

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\sigma} = - \bigg[p - \zeta(\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{u})\bigg] \mathbf{I} + \mu \bigg[\boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u} + (\boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u})^\mathsf{T} - \frac{2}{3} (\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{u})\mathbf{I}\bigg] \end{align}

Where \(p\) is the pressure field, \(\zeta\) is the volume viscosity, \(\boldsymbol{u}\) is the velocity field of the fluid and \(\mathbf{I}\) is the unit tensor.

The \(rr\)-component of the stress tensor is then given by: \begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \sigma_{rr} = - \bigg[p - \zeta (\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{u})\bigg] + \mu \bigg[2 (\boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u})_{rr} - \frac{2}{3} (\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{u})\bigg] \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \sigma_{rr} = - p + 2 \mu (\boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u})_{rr} + \bigg(\zeta - \frac{2}{3}\mu\bigg) (\boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{u}) \end{align}

\((\boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u})_{rr}\) is here the \(rr\)-component of the vector gradient \(\boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u}\), which is given by:

\begin{align} (\boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{u})_{rr}=\frac{\partial u_r}{\partial r} \end{align}

The divergence of the velocity field generally has the following form in spherical coordinates:

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{u} = \frac{1}{r^2} \frac{\partial r^2 u_r}{\partial r} +\frac{1}{r \sin(\theta)} \frac{\partial \sin(\theta) u_{\theta}}{\partial \theta} +\frac{1}{r \sin(\theta)} \frac{\partial u_{\varphi}}{\partial \varphi} \end{align}

Due to the fact that the fluid flows in homogeneously and flows around a sphere, the velocity field around the sphere has cylindrical symmetry. Therefore, the azimuthal derivative is zero when considering the velocity field around the sphere. In addition, it follows from the given initial condition that the fluid flows in along the \(z\)-axis, together with the spherical symmetry of the sphere, that the velocity field and all other relevant vector fields describing this problem cannot have an azimuthal component. This implies for the divergence of the velocity field:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{u} = \frac{1}{r^2} \frac{\partial r^2 u_r}{\partial r} + \frac{1}{r \sin(\theta)} \frac{\partial \sin(\theta) u_{\theta}}{\partial \theta} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \boldsymbol{\nabla} \cdot \boldsymbol{u} = \frac{1}{r^2} \bigg(2 r u_r + r^2 \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial r}\bigg) + \frac{1}{r \sin(\theta)} \bigg( \cos(\theta) u_\theta + \sin(\theta) \frac{\partial u_{\theta}}{\partial \theta} \bigg) \end{align}

Inserting yields for the \(rr\)-component of the stress tensor:

\begin{align} \sigma_{rr} = - p + 2 \mu \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial r} + \bigg(\zeta - \frac{2}{3}\mu\bigg) \bigg(\frac{1}{r^2} \bigg(2 r u_r + r^2 \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial r}\bigg) + \frac{1}{r \sin(\theta)} \bigg( \cos(\theta) u_\theta + \sin(\theta) \frac{\partial u_{\theta}}{\partial \theta} \bigg)\bigg) \end{align}

Since the wanted stresses act on the surface of the sphere, the stress tensor must be evaluated at exactly this position. For the \(rr\)-component of the stress tensor on the surface of the sphere, this results in:

\begin{align} \sigma_{rr}\Big|_{r=R}= - p(r=R) + 2 \mu \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial r}\Big|_{r=R} + \bigg(\zeta - \frac{2}{3}\mu\bigg) \bigg(\frac{1}{R^2} \bigg(2 R u_r\Big|_{r=R} + R^2 \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial r}\Big|_{r=R}\bigg) + \frac{1}{R \sin(\theta)} \bigg( \cos(\theta) u_\theta\Big|_{r=R} + \sin(\theta) \frac{\partial u_{\theta}}{\partial \theta}\Big|_{r=R} \bigg)\bigg) \end{align}

It follows from the viscosity of the fluid under consideration that the relative velocity between the fluid and the object under consideration must be zero at the boundary surfaces. This is a result of the internal friction in viscous fluids, as the shear forces do not allow any relative movement at the boundary surfaces. Due to the fact that the sphere considered here is at rest, the following must therefore apply at the surface of the sphere:

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{u}(r=R,\theta)=\boldsymbol{0}\quad \forall\;\theta\in[0,\pi] \end{align}

This results in the following for the components of the velocity field:

\begin{align} u_r\Big|_{r=R}=u_{\theta}\Big|_{r=R}=0 \end{align}

Furthermore, the disappearance of the velocity vectors on the spherical surface and its spherical symmetry implies that the polar derivatives on the surface also disappear:

\begin{align} \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial\theta}\Big|_{r=R}= \frac{\partial u_{\theta}}{\partial\theta}\Big|_{r=R}=0 \end{align}

This means that the \(rr\)-component of the stress tensor, evaluated at the surface of the sphere, is given as follows:

\begin{align} \sigma_{rr}\Big|_{r=R} = - p\Big|_{r=R} + \bigg(\zeta + \frac{4}{3}\mu\bigg) \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial r}\Big|_{r=R} \end{align}

The \(r \theta\)-component of the stress tensor is given by:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \sigma_{r \theta} = \mu\bigg[(\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{u})_{r \theta} + (\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{u})_{\theta r}\bigg] \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \sigma_{r \theta} = \mu\bigg[\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial u_r}{\partial\theta} - \frac{u_\theta}{r} + \frac{\partial u_\theta}{\partial r}\bigg] \end{align}

On the surface of the sphere, the corresponding component of the stress tensor is obtained:

\begin{align} \sigma_{r \theta}\Big|_{r=R} = \mu\frac{\partial u_\theta}{\partial r}\Big|_{r=R} \end{align}

The \(r \varphi\)-component of the stress tensor is given by:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \sigma_{r \varphi} = \mu\bigg[(\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{u})_{r \varphi} + (\boldsymbol{\nabla}\boldsymbol{u})_{\varphi r}\bigg] \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \sigma_{r \varphi} = \mu\bigg[\frac{1}{r\sin(\theta)}\frac{\partial u_r}{\partial\varphi} - \frac{u_\varphi}{r} + \frac{\partial u_\varphi}{\partial r}\bigg] \end{align}

Taking into account the symmetry properties of the system, the corresponding component of the stress tensor is calculated on the surface of the sphere:

\begin{align} \sigma_{r \varphi}\Big|_{r=R} = 0 \end{align}

Therefore, the normal and shear stresses acting on the surface of the sphere are given by:

\begin{align} &\sigma\Big|_{r=R} = \sigma_{rr}\Big|_{r=R} = - p\Big|_{r=R} + \bigg(\zeta + \frac{4}{3}\mu\bigg) \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial r}\Big|_{r=R} \\[6pt] &\tau\Big|_{r=R} = \sqrt{\sigma_{r\theta}\Big|_{r=R}^2 + \sigma_{r\varphi}\Big|_{r=R}^2} = \mu\bigg|\frac{\partial u_\theta}{\partial r}\Big|_{r=R}\bigg| \end{align}

Normal and shear stresses on a sphere in a protoplanetary disc

Due to the fact that the gases in protoplanetary discs consist to \(99 \%\) of hydrogen and helium (see Owen et al. 2020) and their volume viscosities are negligibly small or zero (see Landau & Lifshitz, Fluid Mechanics, 2nd ed., 1987), it is assumed in the following that the volume viscosity in protoplanetary discs can be considered to be zero:

\begin{align} \zeta = 0 \end{align}

Under these assumptions, the normal and shear stresses acting on a spherical surface in a protoplanetary disc are given by:

\begin{align} &\sigma\Big|_{r=R} = - p\Big|_{r=R} + \frac{4}{3}\mu \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial r}\Big|_{r=R} \\[6pt] &\tau\Big|_{r=R} = \mu\bigg|\frac{\partial u_\theta}{\partial r}\Big|_{r=R}\bigg| \end{align}

Natural units

For the given problem, it makes sense to measure the relevant quantities in units of the object radius \(R\), the velocity at infinity \(u_{\infty}\) and the density at infinity \(\rho_{\infty}\). The corresponding base units, i.e. the units of mass, length and time, are then given by:

\begin{align} \rho_{\infty}R^3 \, , \; R \, , \; \frac{R}{u_{\infty}} \end{align}

It follows then, that the dynamic viscosity \(\mu_{\infty}^*\) at infinity, in the chosen natural units, is given only by the Reynolds number \(\text{Re}_{\infty}\) at infinity:

\begin{align} \phantom{\Rightarrow}\;& \mu_{\infty}^* = \frac{\mu_{\infty}}{\rho_{\infty} u_{\infty} R} \; , \quad \mu_{\infty} = \frac{2\rho_{\infty} u_{\infty} R}{\text{Re}_{\infty}} \\[6pt] \Leftrightarrow\;& \mu_{\infty}^* = \frac{2}{\text{Re}_{\infty}} \end{align}

Since the dynamic viscosity is set constantly to the value \(\mu_{\infty}\) in the entire simulation area, the following relations result for the normal and shear stresses in the chosen natural units:

\begin{align} &\sigma^*\Big|_{r^*=1} = - p^*\Big|_{r^*=1} + \frac{8}{3\text{Re}_{\infty}} \frac{\partial u_r^*}{\partial r^*}\Big|_{r^*=1} \\[6pt] &\tau^*\Big|_{r^*=1} = \frac{2}{\text{Re}_{\infty}}\bigg|\frac{\partial u_\theta^*}{\partial r^*}\Big|_{r^*=1}\bigg| \end{align}

In addition, the speed of sound \(c_{S,\infty}^*\) at infinity, measured in the chosen natural units, is given by:

\begin{align} c_{S,\infty}^* = \frac{c_{S,\infty}}{u_{\infty}} = \frac{1}{\mathcal{M}_\infty} \end{align}

Numerical methods

The simulations carried out as part of this project are performed using the PLUTO simulation software (Mignone et al., 2007). PLUTO is an open source software developed by Mignone et al. (2007). It is used for the numerical simulation of real fluids, i.e. viscous, compressible and thermally conductive fluids. The simulations are carried out by numerical integration of the differential equations underlying the hydrodynamic processes. In this project, a third-order Runge-Kutta method is used for time integration and a third-order finite volume method for spatial discretisation.

Computational domain

As explained a sphere with the radius \(R\) around which a viscous fluid flows with an inflow velocity \(\boldsymbol{u}_{\infty}=-u_{\infty}\boldsymbol{e}_z\) is investigated. Due to the spherical symmetry of the problem, the computational domain is modelled in spherical coordinates, with the centre of the sphere at the origin of the coordinate system. However, due to the axial symmetry, it is sufficient to set up a two-dimensional simulation domain, whereby only the radial component \(r\) and the polar component \(\theta\) are considered.

The grid extends from an inner radius \(R_{\text{I}}\), which corresponds to the spherical radius \(R\), to an outer radius \(R_{\text{A}}\). In the polar direction, the grid starts at an angle of \(\theta_\text{S}=0\) and extends to \(\theta_{\text{E}}=\pi\). The number of cells \(N_r\) in the radial direction and \(N_\theta\) in the polar direction is selected so that the cells have an approximately square shape. This configuration is crucial for the numerical precision of the simulations, as highly distorted cells are more susceptible to numerical errors.

To maximise the efficiency of the simulations, a linearly increasing cell size is used in the radial direction. This ensures a high resolution in the area of particular interest around the sphere, while areas further away from the sphere are displayed with a lower resolution. It follows from the PLUTO User's Guide that the length \(\Delta r_i\) of the ith grid cell in the radial direction is given by the following equation:

\begin{align} \Delta r_i=r_{i-\frac{1}{2}} \big(10^{\Delta\xi}-1\big) \end{align}

Where \(r_{i-\frac{1}{2}}\) is the distance from the origin to the cell wall of the \(i\)-th cell closer to the sphere. In addition, \(\Delta\xi\) is given by:

\begin{align} \Delta\xi =\frac{1}{N_r}\log_{10} \bigg(\frac{R_A}{R}\bigg) \end{align}

In the polar direction, the grid cells in this project have a uniform angular size \(\Delta\theta\). Due to the fact that the length of a cell in the polar direction is given by \(r_i\cdot\Delta\theta\), the length of the cells in the polar direction grows radially outwards to the same extent as the length of the cells in the radial direction \(\Delta r_i\). With a fixed radius \(r_j\), however, the grid cells in the polar direction have the same length \(r_j\cdot\Delta\theta\). The angular size \(\Delta\theta\) results from the quotient of the difference between the start and end angle of the defined grid and the number of cells in the polar direction. The following therefore applies:

\begin{align} \Delta\theta=\frac{\pi}{N_\theta} \end{align}

As already mentioned, the simulation grid represents the area surrounding the sphere under consideration, but not the sphere itself. In order to simulate the problem of the flowing sphere, appropriate boundary conditions must be specified for the system. In this setup, the system is supplied with the so-called reflective boundary condition at the grid’s inner radius. A more detailed explanation of this type of boundary condition can be found in the PLUTO User's Guide. At the outer radius, the corresponding fields are set to the specified values at infinity. The following applies then:

\begin{align} &\rho(R_A)=\rho_\infty \\[6pt] &p(R_A)=p_\infty \\[6pt] &\boldsymbol{u}(R_A)=\boldsymbol{u}_{\infty} \end{align}

Due to the fact that a two-dimensional computational domain is considered because of the axial symmetry of the system, the computational domain has the shape of a half disc with a hole in the origin, of diameter \(2R\). Therefore, boundary conditions must also be specified for the axes \((r,\theta=0)\) and \((r,\theta=\pi)\). The so-called axissymmetric boundary condition is applied there. This boundary condition ensures axial symmetry in the simulations. A more detailed explanation of this type of boundary condition can also be found in the PLUTO User's Guide.

Numerical calculation of the stresses

As PLUTO only outputs the data for the respective cell centres, the pressure and velocity fields in particular are not output on the surface of the sphere. However, these fields are required to calculate the stresses acting on the sphere.

The velocity field on the surface of the sphere is already determined by the boundary conditions. However, the pressure on the surface of the sphere is unknown and must therefore be extrapolated. Linear extrapolation is suitable here, as it has a second-order error which corresponds to the errors of the methods used to determine the derivatives of the fields. For the linear extrapolation of the pressure on the spherical surface \(p(r=R)=p_0\), the next two data points \((r_1,p_1)\) and \((r_2,p_2)\) are required. The extrapolated pressure is then given by:

\begin{align} p_0=p_2+\frac{R-r_2}{r_1-r_2}(p_1-p_2) \end{align}

The derivatives are determined numerically using the Numpy function numpy.gradient. This function can approximate derivatives of functions defined by discrete data points and has a second-order error. A key advantage of this function is its ability to calculate derivatives with inhomogeneous step sizes \(\Delta r_i\). This property is of particular importance in the context of this project, as the cell size in the simulation grid under consideration increases linearly in the radial direction. Correspondingly, the distances between the output data points and thus the step sizes also increase linearly.

For the present investigation, mainly derivatives at the inner edge of the simulation area are required. By default, numpy.gradient uses one-sided first-order differences at the edges, which results in a first-order error there. By setting the parameter edge_order=2, one-sided second-order differences are used instead, so that a second-order error is also guaranteed at the boundary points. A detailed explanation of the exact calculation of the derivatives can be found in the Numpy documentation.

This means that the stresses for each cell in the simulation area, and in particular at its inner edge, can now be determined with second-order accuracy.

Results and discussion

Before the simulations for tuning the Mach numbers can be carried out, a suitable setup must first be found. This setup should be chosen in such a way that, on the one hand, the results are not distorted by the choice of setup and, on the other hand, the simulation duration remains within reasonable limits.

Resolution study

It is to be expected that the simulation data and, accordingly, the results for very coarse grids may be distorted due to the discretisation of the space. It is therefore advisable to first carry out several simulations for grids with different resolutions. The aim is to find the coarsest grid for which the relevant quantities, such as normal stress and shear stress, no longer change or change only slightly. For this purpose, parameters such as the Mach number and the Reynolds number are kept constant in the corresponding simulations.

First, the parameters are selected in line with the bachelor's thesis (Emilio Schmidt, 2024). Specifically, a Mach number of \(\mathcal{M} = 5 \cdot 10^{-3}\) and a Reynolds number of \(\text{Re} = 10^{-2}\) are selected. This choice serves to verify whether the transition to the new system of natural units has been consistent. In particular, it should be ensured that the relevant quantities also converge in this system of units with increasing resolution.

For the first simulation of this resolution study, a grid was selected whose inner radius \(R_I/R=1\) corresponds to the radius of the sphere being flowed upon in the selected natural units and whose outer radius is \(R_A/R=100\). The grid initially contains \(22\) cells in the radial direction, which increase linearly with the outer radius. In the polar direction, there are \(15\) cells of uniform size. In the following simulations, the number of cells in the radial and polar directions is multiplied by a natural number \(n\in\mathbb{N}\). This results in a cell count of \(n\cdot 22\) in the radial direction and \(n\cdot 15\) in the polar direction. In the following, such a grid is referred to as a grid with resolution \(n\).

The following figure shows both the frontal normal stress, i.e. the normal stress acting on the sphere in the direction of flow, and the frontal shear stress across the grid resolution, including a power law fit:

The figure shows that the two quantities converge as the resolution increases. This confirms that the transition to the new system of natural units has been consistent.

In the next step, an analogue resolution study is carried out, but for Reynolds numbers as used in Cedenblad et al. (2021). The same grid and Mach number are used, but the Reynolds number is now set to \(\text{Re} = 10^{3}\) instead of \(\text{Re} = 10^{-2}\).

The following figure shows both the frontal normal stress and the frontal shear stress across the grid resolution, including the power law fit:

The figure shows that both quantities converge with increasing grid resolution even at an elevated Reynolds number of \(\text{Re} = 10^{3}\). However, it is noticeable that convergence is significantly slower than in the case of the smaller Reynolds number \(\text{Re} = 10^{-2}\). In addition, the frontal normal stress exhibits different behaviour. While it decreases or increases in magnitude with increasing resolution at \(\text{Re} = 10^{3}\), it behaves in the opposite manner in the case of \(\text{Re} = 10^{-2}\), increasing or decreasing in magnitude with increasing resolution.

The slow convergence can be explained by the behaviour of the boundary layer thickness \(\delta\), which generally scales with the Reynolds number for both laminar and turbulent flows as follows (see Wikipedia/Boundary_layer_thickness):

\begin{align} \delta \propto \text{Re}^{-a}, \quad a \in (0,1). \end{align}

The exponent \(a\) takes on different values in the interval \((0,1)\) depending on the flow regime, but this is not relevant to the present argument. The decisive factor is that the boundary layer thickness decreases with increasing Reynolds number. Since the distributions of density, pressure and velocity within the boundary layer contribute significantly to the calculation of the stresses under consideration, this must be resolved numerically with sufficient accuracy. Consequently, higher Reynolds numbers require a correspondingly higher grid resolution in order to adequately represent the thinner boundary layer.

The different convergence behaviour can be explained by the fact that the viscosity term, or more precisely the shear viscosity term, scales inversely with the Reynolds number in the normal stress in the selected system of natural units. For large Reynolds numbers, this term is negligible, so that the normal stress on the sphere surface is essentially determined by the negative pressure. As the resolution increases, the cell centres of the cells surrounding the particle move closer to the sphere surface, reducing the error in pressure extrapolation. At coarse resolutions, the pressure is systematically underestimated because the extrapolation is performed from cell centres that are further away from the surface. At low Reynolds numbers, however, the viscosity term cannot be neglected, but rather becomes dominant. Since the fluid is slowed down when it hits the sphere, the radial derivative of the radial velocity component on the sphere surface is positive and thus contributes positively to the normal stress. This derivative increases with increasing resolution for the same reason that the pressure increases at high Reynolds numbers. The cell centres closer to the surface provide more accurate values. Due to the dominance of the viscosity term, this contribution outweighs the increase in pressure, so that the normal stress increases with increasing resolution at low Reynolds numbers or decreases in magnitude.

To be continued...